JOHANNES EBER

This article was originally written for the “Good morning Europe” blog (www.goodmorningeurope.substack.com) by Johannes Eber. We were given permission to publish this article on the European Liberals for Reform blog.

On the news: Portugal shut down its last remaining coal plant over the weekend.

Good news. Phasing out coal is, without a doubt, an important step towards climate rescue. But maybe not as important as we think. Here’s why.

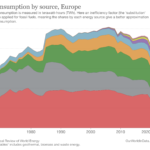

First of all: Where are we today?

Portugal is not the first EU country that ended the use of coal. Belgium, Austria and Sweden are the other three European countries to have already stopped using coal for power generation. That also means that in most countries coal is still burned to generate electricity. “All Europe’s coal plants must close before 2030 in order to meet the goals of the Paris Agreement,” demands Climate Action Network (CAN) Europe, an NGO coalition fighting dangerous climate change, with over 170 member organisations active in 38 European countries. It might not turn out that way. CAN says that just “half of Europe’s 324 coal power plants have either already closed or pledged to shut down before 2030.”

Perhaps such closure scenarios are not necessary to achieve climate protection goals. Because coal-based power generation is part of the EU Emissions Trading Scheme (short: EU ETS). Set up in 2005, the EU ETS is the world’s first international emissions trading system. A cap is set on the total amount of certain greenhouse gases. That cap is reduced over time so that total emissions fall. So if you want to burn coal, you have to buy EU ETS certificates to do so. Since the certificates become fewer over time, coal-based power generation will become more and more expensive as a result of this shortage and thus disappear.

About 40 per cent of the greenhouse gas emissions in Europe are covered with the EU ETS, that is, electricity and heat generation, energy-intensive industry sectors, and commercial aviation within Europe. The EU ETS has brought down emissions from power generation and energy-intensive industries by 42.8 per cent in the past 16 years. Between 2021 and 2030, the plan was to cut the overall number of emission allowances at an annual rate of 2.2 per cent. That would have cut greenhouse gas emissions by at least 40 per cent by 2030 compared to 1990 levels.

But in June this year, EU member states adopted a new climate law which sets a binding Union target of a greenhouse gas reduction by at least 55 per cent by 2030 compared to 1990. To achieve this new, more ambitious goal, the linear reduction factor will be a 4.2 per cent emissions cut every year if started – what is proposed – in 2024. So it is likely, that within a couple of years, there will be no more coal-fired power generation in the EU – with or without final dates.

Instead, the problem lies in the sectors that are not included in the EU ETS. That is gas emissions from homes, cars, small businesses and agriculture. They account for more than half of the greenhouse gas emissions. Unlike the sectors in the EU ETS, these sectors struggle to comply with reduction targets. Because they lack a precise mechanism that ensures a steady reduction in the output quantities.

Coal is bad for the climate. Smoking chimneys, black soot. That is why we are watching the development with excitement. It’s so obvious that it’s bad. But the time of coal power generation is irretrievably running out in the EU. Not much additional political action is needed. Now is the time to pay more attention to other fossil fuels.

Author Profile

-

Founder of the "Good morning Europe blog" and Pixel economist

Guest author for European Liberals for Reform

Johannes' articles are originally written for the “Good morning Europe” blog (www.goodmorningeurope.org) and the Pixel economist (https://thepixeleconomist.substack.com).

We were given permission to publish his articles on the European Liberals for Reform blog.

Latest entries

Post Disclaimer

The opinions expressed by the author of this post do not necessarily represent the opinions and policies of ELfR.