Johannes Eber

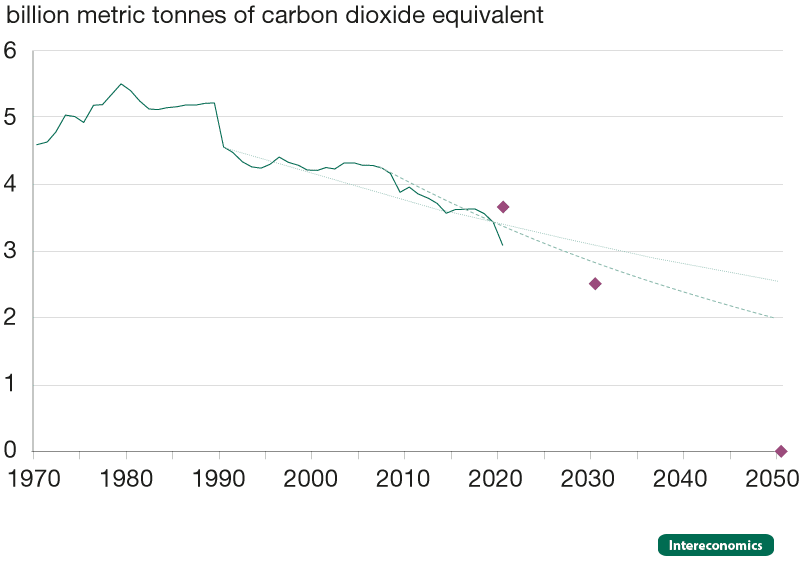

In the chart above you can see the past, the present and the future of the total greenhouse gas emissions from the 27 member states of the European Union.

The solid green line shows the actual emissions from 1970 to the present.

The pink diamonds are the European Union targets for greenhouse gas emission reduction. Net emissions should fall to 45 per cent of their 1990 levels by 2030, and to zero by 2050.

The chart can make one optimistic. The goal for 2020 has been achieved, the plan for 2030 seems reachable – and 2050 is still a long way off.

After having read the paper “Europe’s Climate Target for 2050: An Assessment” by the economist Richard S. J. Tol (from where I took the chart above) I am a bit less optimistic.

Tol is asking what the costs and benefits of the European targets for greenhouse gas emission reduction are.

While reading I have learned that statements about the future are very uncertain in the case of climate issues.

Meeting the targets of the Paris Agreement would cost between 0.5 per cent and 10.5 per cent of GDP in 2050, with a model average of some 3 per cent. This would increase up to between 1 per cent and 21 per cent in 2100, with a central estimate of around 5 per cent.

These costs arise from the CO2 price one has to pay for emitting. This carbon price would rise to €500/tCO2 in 2050, a price increase inflation of 24 per cent per year between now and then, and above €2,000/tCO2 in 2100, a price increase of 7 per cent per year. – In comparison: the current carbon market price is around €80.

It seems the costs of future climate protection are difficult to measure. So are the benefits.

That’s how economists try to measure benefits: they determine the damage done, at the margin, by emitting one more unit of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere. If one now avoids the emission of such a unit, the avoided damage is the benefit.

There are a lot of estimates about the social costs. Tol – who, for his paper, searched through many other papers – counts 5,791 estimates in 201 papers. The mean of all estimates is €42/tCO2.

Accordingly, the current benefit of a ton of CO2 not emitted would be €42.

Since this is below the current carbon market price of around €80, one could argue that the costs of EU climate policy exceed the benefits. But this statement may be too simple because of the poor prediction about the future.

In fact, I was less fascinated by the numbers in Tol’s paper than by his arguments about the difficulties in reaching the European Union targets.

Looking at the chart above, it seems quite possible that the European Union will achieve the goals it has set itself. But the chart is missing some information.

A first challenge can still be seen in the chart. Do you see the dotted and dashed light green lines? These are simple trend projections. They show what will happen when we move on in the future as we did in the past. As you can see, the lines do not hit the pink diamonds. So the curve will have to go down increasingly steeply. Between 1990 and 2019, greenhouse gas emissions fell by 1 per cent per year. This accelerated to almost 2 per cent per year between 2007 and 2019. The 2030 target requires that the rate of decarbonisation doubles again, to nearly 4 per cent per year. The 2050 target is more ambitious still.

But the challenges are even bigger than the pure percentages show. The low-hanging fruits may have been picked. Renewable sources of electricity are the main reason for the drop in past emissions. Electricity is probably the easiest sector to decarbonise. Decarbonisation is harder for transport, heating, industry and agriculture. Tol: “A doubling of the decarbonisation rate requires much more than a doubling of the policy effort.”

What do we learn from these numbers and arguments? The wide range of estimates suggests that we still know relatively little about the difficulties ahead of us. Rescuing the climate can be very expensive. That is also why achieving the reduction targets at the lowest possible cost is very important.

That is all the more important since most science reckons with these lowest possible costs. Their estimates assume cost-effective implementation of climate policy. This is far from reality. Tol: “Governments routinely violate this principle, with different implicit and even explicit carbon prices for different sectors and for differently sized companies within sectors.”

Maybe good politics has never been more important than today.

Author Profile

-

Founder of the "Good morning Europe blog" and Pixel economist

Guest author for European Liberals for Reform

Johannes' articles are originally written for the “Good morning Europe” blog (www.goodmorningeurope.org) and the Pixel economist (https://thepixeleconomist.substack.com).

We were given permission to publish his articles on the European Liberals for Reform blog.

Latest entries

Post Disclaimer

The opinions expressed by the author of this post do not necessarily represent the opinions and policies of ELfR.