JOHANNES EBER

This article was originally written for the “Good morning Europe” blog (www.goodmorningeurope.substack.com) by Johannes Eber. We were given permission to publish this article on the European Liberals for Reform blog.

How would the corona pandemic have gone if it had been fought centrally at the European level? What would our landscapes in Europe look like if agricultural policy took place primarily at a national level and not, as currently, at the European level? Can the EU as a whole combat climate change effectively? Would a European-wide common minimum wage provide higher wages or lead to job losses? Do we need an EU-army? At what political level should school education be determined – on the union, national, regional or local level?

The list of questions could go on and on. Generally speaking, all questions can be summarised in one:

How should decision-making for public sector activities be distributed among different levels of government?

In the context of Europe, the questions can also be phrased as the following: For which tasks do we really need the European Union – and for which ones not? What would a European Union look like if it was not shaped by history but designed by scientific knowledge?

Since these are tough questions, I delved into that topic for several days (and didn’t publish here on Good Morning Europe in the meantime). Here is what I found out.

I would like to start by answering, in short, an even broader question: What is the state’s role anyway?

For economists, the answer is simple: providing public goods and redistribution.

Examples of public goods include fresh air, knowledge, national defence, flood control systems, legislation and street lighting. What is special about public goods is that everyone can easily enjoy the benefits of these goods. In addition, the consumption by one individual should not affect the consumption of another individual.

Two properties characterise public goods: they are non-rivalry and non-excludable.

Since public goods are made available to all people – regardless of whether each person individually pays for them – private markets do not provide such goods.

The state is necessary here.

It is similar with redistribution. Since market outcomes are often viewed as unfair, the state redistributes parts of that outcome (mainly by collecting taxes).

Interim conclusion: From an economic perspective, the state has a twofold justification. First, the provision of goods and services that would not exist without it, and, second, the establishment of justice through redistribution.

After these preliminary considerations, we now get to the core that answers the following question: At which level of government should which political activity be located?

The European Union itself has an answer. It is laid down in Article 5 (3) of the Treaty on European Union:

“Under the principle of subsidiarity, in areas which do not fall within its exclusive competence, the Union shall act only and in so far as the objectives of the proposed action cannot be sufficiently achieved by the Member States, either at the central level or at regional or local level, but can rather, by reason on the scale of effects of the proposed action, be better achieved at Union level.”

With that treaty text, the EU has limited itself.

The means of that self-restraint is the principle of subsidiarity. What is this principle about?

That’s what Wikipedia says:

“Subsidiarity is a principle of social organisation that holds that social and political issues should be dealt with at the most immediate (or local) level that is consistent with their resolution.”

The philosopher Peter Rinderle puts it more clearly in his worth reading paper “The Political Philosophy of European Subsidiarity“:

“The core idea of subsidiarity is to allocate to and exercise political authority at the smallest level of a particular community, unless there are reasons to the contrary.”

Why should this be a good idea?

There are several reasons.

Moral argument: By allocating political authority to the local level, subsidiarity can be a safeguard against tyranny and oppression. Central authorities can develop a tendency of intervening excessively and illegitimately in the affairs of their subjects and thereby restricting their freedom. “Distributing power on many shoulders is meant to prevent this development from happening,” Rinderle writes.

Political argument: Local governance allows higher participation of those affected by political decisions. Plus, the variety of interests is better facilitated by smaller units of government.

Economic argument: This is very close to the political argument. Centralised decisions can be inefficient. Imagine, cultural activities for the whole EU were planned in Brussels. Such a uniform centralised decision about the level of state-subsidised cultural activities would probably not respect the variety of citizens’ preferences in the different member countries. The choice and amount of cultural subsidies appropriately chosen for one area wouldn’t represent the wishes of the people of another area. Hence, central planning would be inefficient, and it would be better to leave the decision about these activities to each area.

Albeit there are good arguments to strengthen and protect the powers of its lower levels, not every political activity is rightly placed on the lowest level (otherwise only this lowest level would be needed). So what is the decision criterion for putting a political activity to a higher level, that is, regional, national, union or global?

To answer this question, we need to look again at the property of public goods. Remember, they are jointly consumed, and the costs of providing such goods are to be shared among the inhabitants of the area or jurisdiction.

Suppose that the decisions about providing a public good are made in a smaller area and thus by a smaller group than the geographical distribution of benefits would dictate, then some benefits from the good and some potential contributors to its costs are not considered. Consequently, the provision and outcome of the public good activity are inefficiently low. This is the main reason to put political activity at a higher level.

Think of climate change. If the fight against climate change was organised mainly on a local level. Each community would consider the costs of reducing their emissions compared with the benefits of that reduction. Because the costs arise at the local level, but the benefits at the global level, rationally behaving individuals would hardly reduce emissions. Overall efforts would be way too little. Fighting climate change has to take place at the highest possible level.

To summarise the preceding theoretical part:

1) Public goods are provided most efficiently on that political level with control over the minimum geographic area that would internalise the benefits and costs of its provision.

2) What the appropriate level is – global, union, national, regional or local – depends on the nature of the public good.

From theory to practice. We have learned that there should be Union-level decision making for which the geographical distribution of benefits of a public good extends widely across different nations within the union.

What does this mean for European Union policy? Which public goods should be provided on that European level?

In the following, I discuss some policy areas that are often addressed to the highest possible political level or are currently in place at the European level.

Common market: The European single market provides a major reason for the centralisation since it ensures a common level playing field for all market participants. It guarantees the free movement of goods, capital, services, and people, known collectively as the “four freedoms”. In general, the EU is doing quite well on that.

National defence and foreign policy: Strong defence on a union level has some advantages. Compatible weapons systems and common weapons development strengthen defence readiness and save costs. If the citizens of the different states have similar ideas about defence policy, a common defence policy makes sense. Efforts are being made at the European level to establish European armed forces. But that is still in their infancy. The EU’s role is quite limited in national defence and security since NATO has had this role already for many years. Plus: Some EU countries are not members of NATO, which makes the part of the EU fairly complex.

Internal security and border control: With the Schengen agreement (signed in 1985) in place, the benefits from joint decision-making about the forms of border control are apparent. Border checks within the EU were largely abolished. And it allowed vehicles to cross borders without stopping, allowing residents in border areas freedom to cross borders away from fixed checkpoints and the harmonisation of visa policies. As successful as the Schengen Agreement is, a common European policy at the EU’s external borders is just as tricky. For far too long, those European countries that have hardly been affected by the flow of refugees have not taken care of the problems. That seems to be changing. But the road to a common refugee policy and joint protection of the external borders still seems long. Also because the political interests of the various governments are quite different.

Networks: Freeways and rail transport networks, electricity networks and communication networks – the establishment of common standards for networks is one of the most important tasks of the European Union. Since networks or standards naturally extend beyond national boundaries, the appropriate level of governmental decisions will be the union level. And the EU takes on this task. In this context, one thing becomes apparent: the EU’s strength is not its financial strength (the EU budget is smaller than the budgets of Austria or Belgium), but its ability to standardise. The total number of EU legislative and non-binding acts has shown significant growth over the years. A relevant part of this increase relates to such regulations. The EU is often laughed at or even despised for regulations down to the smallest detail – the advantages of standardisation, on the other hand, are often overlooked.

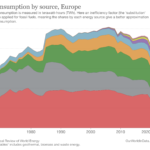

Environment: As said above, fighting global warming and any other global externality is an EU level duty. The EU is the natural party in international negotiations to control a global environmental externality. And the EU is not bad with it.

Agriculture: Agricultural subsidies are the foreign body of EU policy. Still, the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) takes 35 per cent of the EU Budget (at least this percentage is falling continuously). Agricultural subsidies are not justified at the European level – either on lower levels. Agricultural products are simply not public goods.

Taxes: There is a massive debate about whether taxes should be harmonised across Europe. It is argued that independent countries have strong incentives to reduce tax rates for mobile factors and that this would lead to too low levels of some forms of taxation and too high levels for others. On the other hand, low taxes can be an important lever to attract foreign capital for less developed countries. However, there are few efforts to harmonise taxes within the EU. One of them, the Value-Added Tax (VAT), with a minimum standard rate of 15 per cent and a restricted list of reduced rates in all EU member countries.

Labour markets, social standards, the welfare state: In these areas, not the EU but the national governments are in charge. As in other areas, the trend here is also towards the European level. For example, there is currently an initiative to introduce a European-wide minimum wage. Such initiatives need to be well thought out. It is often argued that poorer countries practise “social dumping” by having lower social standards or wages and thereby gain an unfair competitive advantage by avoiding the costs of higher standards. But a fraction of jobs in poorer countries would become unprofitable following the imposition of higher wages and social standards, leading to unemployment and emigration out of this area. But with the harmonisation of living conditions in the EU, common standards and a common welfare state will become more likely – and more meaningful.

In general, the subsidiarity principle might conflict with a European welfare state. The principle of subsidiarity can be in contradiction to values such as equality or social solidarity. The more power is allocated to and exercised at the lower levels of a society, the less power is available to remedy political problems which are of common concern for all members of a community. The correction of inequality through the welfare state might be such a common concern. It is not by chance that the so-called welfare state emerged together with the central state.

“The idea of subsidiarity meant to protect and support the autonomy of local agents can create a conflictual relationship with the value of national solidarity and redistribution,” Peter Rinderle writes.

Bottom line: It will be interesting to see how the European Union will develop based on its self-imposed principle of subsidiarity. My impression is: Much of what is at the European level has developed historically, but most of it corresponds to the principle of subsidiarity. That may be less applicable to the European budget (with its high agricultural budget), but that budget matters less anyway. And that science can, at best, set the guard rails to the central question of which political activity shall take place on which level. Rinderle again: “Subsidiarity cannot be approached solely from the distant perspective of an airplane flying above the dire, dark and harsh realities of politics. Instead, the analytical ‘devil’ is hidden in the details of institutional implementation.”

Author Profile

-

Founder of the "Good morning Europe blog" and Pixel economist

Guest author for European Liberals for Reform

Johannes' articles are originally written for the “Good morning Europe” blog (www.goodmorningeurope.org) and the Pixel economist (https://thepixeleconomist.substack.com).

We were given permission to publish his articles on the European Liberals for Reform blog.

Latest entries

Post Disclaimer

The opinions expressed by the author of this post do not necessarily represent the opinions and policies of ELfR.