🇷🇸 / Novak Djokovic / #73

When I was a teenager, Germany had an athlete as a national hero: tennis player Boris Becker. I had never been interested in tennis, Germany had never been interested in tennis.

That changed in the summer of 1985. Becker became a star overnight when he won Wimbledon at the age of 17, the youngest champion in tournament history (that record still stands today). I was sitting in front of the television for hours on end. So did millions in Germany.

From today’s point of view, it sounds strange, but when Boris was playing, it was Germany playing. That’s how I felt. That’s probably how a majority of Germans felt. When he won, we won; when he lost, we lost; when he was praised, we were praised; when he was criticised, we were criticised. Sports fans are odd sometimes. I was odd.

Therefore I have some understanding of the Serbs and their complaints of how their hero Novak Djokovic had been treated. His quest for a 10th Australian Open tennis championship remains undone by his decision to stay unvaccinated against Covid-19.

At the beginning of the week, he landed in Belgrade after being deported from Australia following a decision of the Australian government to revoke his visa out of concern that he might inspire anti-vaccination sentiment.

While the world wonders how a superstar can be so insensitive and try to enter Australia by court order, a country that is currently experiencing the worst of the pandemic, a country that had in the course of the pandemic banned all travel to the country (even to Australians, leaving families separated for months). So while almost the whole world doesn’t understand Djokovic’s behaviour, Serbia celebrates its hero.

Why?

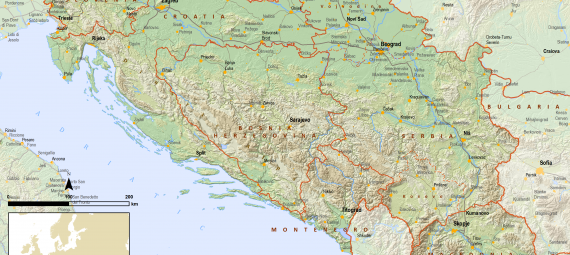

First of all and as always, we must not tar everyone with the same brush. There aren’t THE Serbs. The landlocked country in Southeast Europe with its almost seven million inhabitants is as diverse as any other country. Many support their tennis star unconditionally, many criticise him.

But Serbias’s media is not diverse. It is increasingly brought into line.

Andrew Higgins, New York Times’ bureau chief for East and Central Europe, wrote a frightening piece about Serbia this week.

“Government loyalists run Serbia’s five main free-to-air television channels, including the supposedly neutral public broadcaster, RTS.”

According to Higgins’, a survey of Birodi, an independent monitoring group, is saying that on Serbian television over a three-month period from September, Serbian president Aleksandar Vučić was given more than 44 hours of coverage, 87 per cent of it positive, compared with three hours for the main opposition party, 83 per cent of which was negative.

To the New York Times, Zoran Gavrilovic, the executive director of Birodi said that Serbia has “become a big sociological experiment to see just how far media determines opinion and elections.”

Those elections are ahead. On 3 April 2022, general elections will be held for both the president and National Assembly.

As Minister of Information under the Slobodan Milošević administration, Vučić introduced restrictive measures against journalists, especially during the Kosovo War. The methods might have changed, the aim stays the same: to maintain power by influencing the media.

Like in Poland and Hungary, those in power have succeeded in establishing fawning coverage. The V-Dem Institute, a Swedish independent research institute, is now ranking Serbia, Poland and Hungary among its “top 10 autocratizing countries“. And Freedom House, a non-profit, majority U.S. government-funded organisation, now classifies Serbia as “partly free.”

So Serbian media is one-sided. It tends to have populist views. Views that President Vučić proclaims. Therefore the impression of Non-Serbs that most Serbs have no understanding of Australia’s reaction but full understanding for their tennis star is at least in parts shaped by government influenced media and politics. It’s the impression of what the media says, not what the people think.

But at least in part, the media will reflect the mood of the population.

There might be a reason for Serbian’s oddity. It’s past.

Serbia is in some ways the leftover of former Yugoslavia. Back then, it was its core. Serbia inhabits the former Yugoslav capital Belgrad, Serbia continued to use the national anthem after the breakup of Yugoslavia (but only until 2006 when Serbia and Montenegro became independent states), and the Kingdom of Yugoslavia (from 1918 till 1941) was ruled by a Serbian dynasty (called Karađorđević).

Serbs were once powerful and the heart of Tito’s Yugoslavia. With the end of the Soviet Union, most individual republics turned away, including the western world that took sides against the Serbs during the Yugoslav Wars. At least that’s how many Serbs may think and feel.

By the way: that’s how Russians may feel too. Russia was the heart of the global power Soviet Union. From the perspective of Russia as the de facto successor state to the Soviet Union, it has lost 14 countries (Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Estonia, Georgia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Latvia, Lithuania, Moldova, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Ukraine, Uzbekistan). From this point of view, Serbia has lost six countries. It may therefore not be a coincidence that today Russia and Serbia are connected tightly.

Probably such self-awareness doesn’t do justice to history. But people’s feelings don’t always follow history. Like me as a teenager crossing my fingers for Boris Becker in the 1980s watching him play on the tennis court. Watching Germany play against the rest of the world. That’s how it felt back then, forty years after the end of Nazi Germany, with the Federal Republic of Germany still looking for a place in the world order. This may sound far-fetched, but 1980s Germany was still in search of positive recognition.

So, because of my past, I may have some understanding of Serbia. I am convinced understanding helps Serbia. It supports democracy. Because people who otherwise condemn Serbia lock, stock and barrel are playing into the hands of populists. It feeds their stories of hostile foreign countries.

Author Profile

-

Founder of the "Good morning Europe blog" and Pixel economist

Guest author for European Liberals for Reform

Johannes' articles are originally written for the “Good morning Europe” blog (www.goodmorningeurope.org) and the Pixel economist (https://thepixeleconomist.substack.com).

We were given permission to publish his articles on the European Liberals for Reform blog.

Latest entries

Post Disclaimer

The opinions expressed by the author of this post do not necessarily represent the opinions and policies of ELfR.