Johannes Eber – Good morning Europe blog

Much of the world wants to prevent Putin’s Russia from invading Ukraine. The means of prevention: setting the price, Putin would have to pay, as high as possible.

The west has ruled out military means to inflate the price. For a good reason. The costs of a military conflict between Russia on the one hand and Europa and the USA on the other would be immense, not just for Putin. Russia is still one of the most powerful militaries in the world. In 2020, it spent more than 60 billion US-Dollar on its military, accounting for 11.4 per cent of government spending. Plus, Russia is still a nuclear power.

What remains is the threat of economic sanctions. The rationale behind is the same as with the threat of military force: to drive up the expected negative (economic) consequences so that Putin refrains from attacking.

The problem with sanctions is that they work reciprocally, on those who sanction and on those sanctioned. If you prohibit a country from transporting goods into your country, the citizens of your country can’t enjoy those goods. In addition, the sanctioned country will probably take countermeasures.

Despite this reciprocity, sanctions can be a powerful tool to impose interests. Sanctions are usually effective when many countries sanction one country. Then sanctions can be chosen that are not very painful for each of the many countries, but – in total – very painful for the sanctioned country.

Example: The country to be sanctioned gets half of its exports from grain. Suppose the sanctioning countries stop buying this grain (and instead buy elsewhere on the global market). In that case, the losses for the sanctioned country are significant but manageable for the sanctioning countries.

That’s the theory. The practice is more complex. For example, the market structures of the sanctioning states are different. Therefore sanctions affect the individual states differently.

This is the case in the European Union. Russia is the biggest export market for Latvian goods and the second-biggest for Lithuanian products. Trade restrictions as a result of sanctions would hit the two countries hard. The large European economies would be significantly less affected by such restrictions. Less than 2 per cent of goods exports from Germany, Italy or France go to Russia. Overall, Russia is the bloc’s fifth-largest export market, accounting for about 4 per cent of its good exports. Conversely, it looks different: The EU is Russia’s biggest trade partner, accounting for 37 per cent of the country’s total trade in goods with the world.

So, at first glance, the matter is straightforward: Russia is more dependent on Europe than vice versa. But things are no longer clear if you take a closer look.

Russia is still a one-dimensional economy. It is dependent on the export of oil and natural gas. They account for two-thirds of its exports.

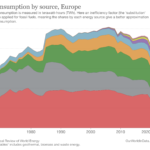

Such a one-dimensional economy is an easy target for sanctions. The sanction is easy to set, and the affected country will be hit hard if it can no longer find buyers for its main products. The problem in the Russia case: Europe relies heavily on these main products.

About 40 per cent of the bloc’s natural gas imports and nearly one-third of its crude oil imports come from Russia.

The dependencies are therefore strongly mutual. With differences in the temporal effect. Europe could be severely affected if delivery stopped. Emergency rationing and blackouts could occur in the short term. In the long term, Russia would have to deal with permanent revenue losses. Because, if Russia wasn’t a reliable energy supplier, buyers would permanently look for other energy supply options.

Such a turn is the worst-case scenario for Putin. His power is based on oil and gas. Also because most of these companies are at least partially owned by the state. The revenues from these companies flow directly into the state budget – allowing Putin to secure his power by spending money on those who support him.

So, because oil and gas keep Putin in power, he won’t turn off the tap. And since neither side is interested in stopping the exchange of these commodities, oil and gas will not decide the Ukraine conflict. Due to the great interdependence, they are simply not suited as a means of pressure.

What looks like a stalemate is more likely to benefit Putin. If Russia’s main export products can be less sanctioned, the overall effect of the sanctions will be weaker. Europe would do well to reduce its dependence on Russian raw materials as soon as possible.

Author Profile

-

Founder of the "Good morning Europe blog" and Pixel economist

Guest author for European Liberals for Reform

Johannes' articles are originally written for the “Good morning Europe” blog (www.goodmorningeurope.org) and the Pixel economist (https://thepixeleconomist.substack.com).

We were given permission to publish his articles on the European Liberals for Reform blog.

Latest entries

Post Disclaimer

The opinions expressed by the author of this post do not necessarily represent the opinions and policies of ELfR.