by Johannes Eber – The Pixel economist

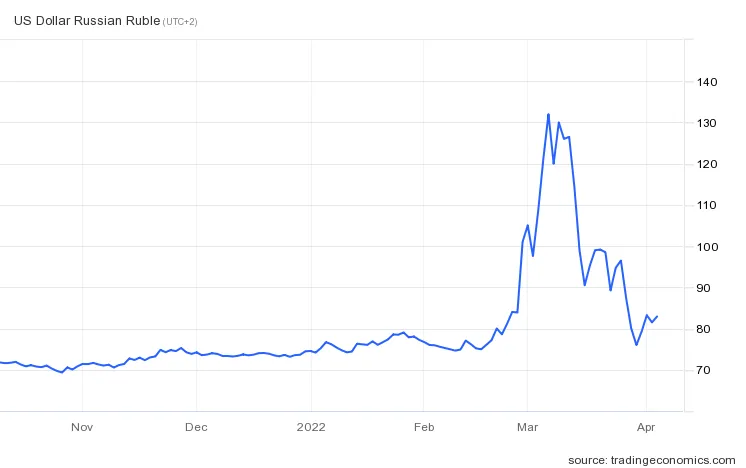

At the beginning of the war in Ukraine, the Russian currency ruble lost almost half its value compared to the US-Dollar. In the meantime, the ruble has almost completely made up for the loss.

How is that possible? Do the money market trading people believe that the Russian economy will recover soon?

Very likely not. Instead, the Russian central bank managed to recover the ruble. But the price will probably be high.

Here is what the central bank did (exactly, “The Central Bank of Russian Federation“) and what will happen as a result.

On 28 February 2022, the central bank raised the key interest rate — that is the rate at which banks can borrow money from the central bank — from 9.5 to 20 per cent.

This induced people to keep their funds in Russia. That’s because the central bank’s interest rate determines the interest level in a country. The higher the interest level, the more attractive it is to lend money in this currency. Thus, the demand for rubles was supported by the central bank’s move.

Secondly, the central bank has imposedextensive controls to prevent capital flight. Russians have been prohibited from moving money to foreign bank accounts, extracting more than 10,000 US-Dollars in international currencies over the next six months, or taking more than that sum out of the country in cash. Plus, banks and brokers have been temporarily banned from operating cash-based foreign exchanges for dollars and euros.

This widespread ban on Russians exchanging rubles for foreign currency has also supported the ruble exchange rate.

But this monetary policy of the Russian central bank comes at a high price.

For understanding this it helps to look at classic propositions in international economics called the “impossible trinity“.

The “impossible trinity” is a proven concept in international economics that states that it is impossible to have all three of the following at the same time:

- a fixed foreign exchange rate,

- free capital movement (absence of capital controls),

- an independent monetary policy.

The concept was developed independently by British economist John Marcus Fleming in 1962 and Canadian economist Robert Alexander Mundell in different articles between 1960 and 1963 (more here).

The essence of the concept is that a central bank can only pursue two of the above-mentioned three policies simultaneously.

These are the options a central bank has:

- a stable exchange rate and free capital flows (but not an independent monetary policy because setting a domestic interest rate different from the world interest rate would undermine a stable exchange rate due to appreciation or depreciation pressure on the domestic currency)

- an independent monetary policy and free capital flows (but not a stable exchange rate)

- a stable exchange rate and independent monetary policy (but no free capital flows, which would require the use of capital controls)

Interestingly, the Russian central bank has given up two goals at the same time in order to reach the third goal: It has abandoned both the free movement of capital and independent monetary policy (by raising interest rates to 20 per cent) to achieve a stable exchange rate.

Probably this will severely damage the Russian economy. Without the free movement of capital and investments (because investing becomes very expensive because of the high interest rates), the economy will likely collapse.

Why is Russia willing to pay this high price?

Economist Paul Krugman assumes in the New York Times that this is because the ruble rate is of great importance to Putin and because the ruble rate is evident to everyone.

Krugman:

“My guess is that the value of the ruble has become a crucial target not so much because it’s all important but because it’s so clearly visible.”

The chain of arguments goes on that the ruble exchange rate cannot be kept secret, but other economic data can.

Krugman again:

“If Russia’s economy deteriorates as badly as most expect in the near future, it seems all too likely that the nation’s muzzled media will simply deny that anything bad is happening. One thing they couldn’t deny, however, would be a drastically depreciated ruble. So defending the ruble, never mind the real economy, makes sense as a propaganda strategy.”

In other words: Putin can sell the current ruble exchange rate as a success. Look here, sanctioning West, you can’t harm us, Putin can say, while he will try to prevent other economic data from becoming public.

Krugman doesn’t think this strategy is wise:

“Russia’s defense of the ruble, while impressive, isn’t a sign that the Putin regime is handling economic policy well. It reflects, instead, an odd choice of priorities, and may actually be a further sign of Russia’s policy dysfunction.”

Author Profile

-

Founder of the "Good morning Europe blog" and Pixel economist

Guest author for European Liberals for Reform

Johannes' articles are originally written for the “Good morning Europe” blog (www.goodmorningeurope.org) and the Pixel economist (https://thepixeleconomist.substack.com).

We were given permission to publish his articles on the European Liberals for Reform blog.

Latest entries

Post Disclaimer

The opinions expressed by the author of this post do not necessarily represent the opinions and policies of ELfR.